Asa Smith, “the strange mystic of Clarendon,” had a vision of “chalybeate water impregnated with lime” that would lead him in 1776 to discover the springs in the western part of town that would cure his “scrofulous humor” (cancer).

Five years later, a business-savvy Mr. George Rounds, saw the potential of the area after another man, a Mr. Shaw, was also cured of cancer by anointing himself with the clay surrounding the springs. He built a simple log cabin and took in as boarders those who traveled in search of a cure and in doing so gained the distinction of opening the first spa in the state of Vermont. By 1798 business was going so well that he built a hotel which could house twenty guests. By this time eight families had moved nearby, each having enough children (averaging 14 each), to warrant building a school house.

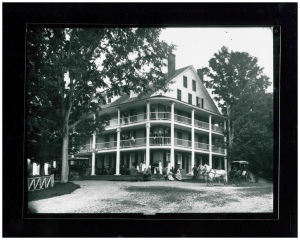

In 1834, a three-story hotel was built, either by Thomas McLaughlin or Richard Murray (I found both). Fashioned in a Southern style with grand columns and two stories of wrap-around verandahs, it began to attract national attention. Thanks to the booming railroad industry, visitors would come into the lush green mountains from the cities to escape the summer heat. Among them were many from the Deep South. As other buildings were added to the grounds, 500 guests could be, and were at times, accommodated.

In 1839, an official analysis of the spring water was conducted, and a report by a Mr. Augustus Hayes of Ruxbury, Mass. found that the waters, averaging 52 degrees, were “more pure than river waters.” “Their curative powers,” he wrote, “are derived from their aerial constituents, which are remarkable.”

Given that their “curative qualities result more from gaseous than mineral characteristics,” the report states that “Mr. Hayes well considers the Clarendon water as ‘remarkable for composition;’ — and also, that ‘they differ somewhat in composition from any heretofore known.’”

“We may perhaps, then,” the report continues, “infer that their sanative powers may also be remarkable.” To corroborate this statement the report includes case studies of guests who, taking tumblers of the water daily, found almost instant relief from such maladies as skin inflictions, lung complaints (including consumption), coughs, and swollen limbs and joints.

No doubt as a result of this report, the 1840s and 1850s saw a boom in Clarendon House’s business.

Then in 1861, the Civil War broke out. Hotels and the other curative spas, which during the 1850s “were burgeoning all over the state,” closed due to a lack of patrons. While fire took many of the buildings after the war, “the fact that few Southerners cared to return to abolitionist Vermont after the Civil War was another important factor.”

However, Clarendon House (or Clarendon Springs Hotel) remained open. Not only that, it appears that it had a resurgence.

In 1866, the hotel was purchased by Byron (or Richard) Murray. Obviously an astute business man, he built a bottling house and began shipping “Clarendon Natural Mineral Spring Water” by bottle and barrel by train to the cities where it was consumed as an appetite stimulant and digestive aid.

One year later, a New York Times article from August 29, written by a mysterious “C,” declares Clarendon Springs “one of the pleasantest places to which can resort during the summer, to avoid the heat, and dust, and noise, and other annoyances of the Great City.”

When “C” declares that “Mr. Murray, the gentlemanly proprietor of the Clarendon House knows ‘how to keep a hotel,’ which is perhaps the highest praise that can be bestowed on a landlord,” one wonders if this article was not part of a well-executed marketing plan. Indeed, it was under his management that Clarendon Springs became a “mecca of fashion” with notables such as

J.P. Morgan vacationing as one of the 2,500 annual visitors. One of the “foremost watering-places in the country,” Clarendon boasted “pleasant picnics and excursions,” music, dancing, golf, tennis, and other such entertainments, as well a “display of rich toilettes on the part of the ladies.”

Under the care of the Mr. Murray’s sons, the hotel continued to thrive, its popularity “at its height during the ‘Gay Nineties,’” and indeed many of the photographs provided by the Rutland Historical Society are from 1890.

Exactly when the hotel closed is unclear. One source states that it closed in 1898. However, a June, 1900 news clipping from the New York Tribune lists the Clarendon Springs House, which was open each June to October, as a “resort of much attractiveness and healthfulness.” But by 1940, according to a book about the Fish family, one member of which played with the Ira band who regularly performed at the hotel, there were only a few residents remaining in the area after the “Springs went into decline.”

The hotel, which once held a grand ball room and 120 guest rooms, but became a “vandal-torn wreck,” is apparently now gutted. But with help from the Vermont Historical Society, the present owners have spent the past thirty-odd years restoring the exterior back to its former grandiose and beauty. It is now, along with its various outbuildings, for sale.

And the Springs? They continue to bubble away.

A SIDE NOTE

History, like any telling of a story, can have many versions. It can become a detective game. The truth sometimes lies buried in between the “knowns.”

One interesting ambiguity: The New York Times article from 1867 claims the waters were discovered just fifty years earlier, “by accident” and had been kept “in obscurity.” The fact that Asa Smith quite deliberately found them almost fifty years before that and had been quite far from “obscure,” apparently didn’t fit the marketers’ desired message (what that was exactly, is hard to know), and so the truth was watered down… so to speak.

Also in my research, I found two references to the fact that Clarendon Springs was a “known” stop on the Underground Railroad (UGRR). Referencing the many Southern visitors, one source explains that they would sometimes bring their house servants/slaves along with them. According to this story, the general store next to the hotel was a safe spot for runaway slaves. Another source claims the exact location of the Clarendon Underground Railroad is still a secret.

So secret, in fact, it isn’t even corroborated anywhere in the UGRR literature. The closest documented safe house was in Wallingford. So, where and why would this rumor/story begin? And is there an ounce of truth to it? We may never know.

Information for this story was found in “History of Rutland County,” 1886 by Smith & Rann, “These Wonderful Waters,” Vermont Life, Summer 1957 by Lousie Koier, “Observations Made During a Visit to Clarendon Springs, VT,” 1840 by Joseph Gallup, M.D., and various other sources provided by Rutland Historical Society.

Originally published 5/7/14 Rutland Reader | (c) Joanna Tebbs Young

It turns out Asa smith is my grandfather(many times removed) so it is fun to learn all I can about him.

My father, Walter Clarence Ewing (1905-1960), told me that as a young boy he went with his father, Walter Charles Ewing, to the Clarendon Springs Hotel delivering milk.