Part 1 of two stories on the Rutland Trolley. See Part 2 here.

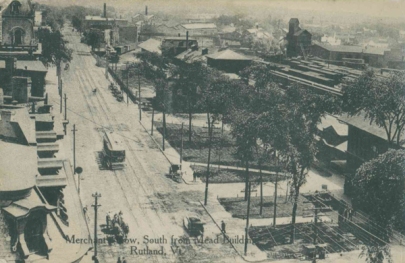

When the street was dug up in front of Green Mountain Power’s new Energy Innovation Center on Merchants Row in the fall of 2013, the workers hit steel. Hiding just below the asphalt on which we daily drive our (one- or two-person, gas-guzzling, road-hogging) cars, they had discovered tracks to another time: The Trolley Era.

It was a short-lived era in Rutland; approximately 40 years, from 1882 to 1924, with its heyday spanning from 1913 to 1916. But the trolley was an innovation that changed the scenery and infrastructure of Rutland County, where people built their homes, and the way in which they spent their weekends.

Putting the horse first

It all began in 1882 when the idea and legislation for a Rutland street railway came together. The Rutland Horse Railroad Co. cantered into town with president E. Pierpoint at the reins in July 1885. The first tracks were laid later that year and on December 12 at 7 p.m., the fifteen-passenger horse cars went into operation. That evening, with their lamps glowing—red for the in-town City Line and green for the Main Line to West Rutland—and the entire next day, a snowy Sunday, the five cars carried a total of 1,000 excited passengers.

The cars, built in Pennsylvania, with their attractive paint jobs of yellow with red trim, comfortable upholstery, and small coal stoves, were apparently a pleasant surprise for the people of Rutland. Despite frequent derailings, the cars ran the five and half miles every hour from the fairgrounds to West Rutland for a cost of eight cents, and every half hour on a two and a half mile loop from Church to Crescent to Main to Madison to Merchants Row for five cents. Eventually a South Belt line was also built to accommodate the 2,000 parishioners of St. Peter’s Catholic Church on Meadow Street.

It’s electrifying

Not even a decade later, Rutland was ready to try something new. After Richmond, Va. had instituted the first successful electric streetcar system in 1887, horse railroads around the country also converted to electric in quick succession. Rutland became the second Vermont streetcar company—after Burlington a year earlier—to become electrified. In accordance with their new role, the Rutland Horse Railroad Co. was renamed Rutland Street Railway.

New rails were laid, new, heavier and larger cars ordered, and generators were positioned on Cleveland and West streets. On November 19, 1894, five twenty-eight foot, twenty-six passenger cars arrived. Painted yellow with silver lettering and heated with small stoves like their predecessors, the interiors of these newer cars were finished in birch and lighted with electricity. Service began on November 26 carrying passengers around town every twenty minutes and to West Rutland every hour.

That Wednesday, November 28, 1894, the Rutland Herald reported: “There was lots of riding on the electric cars yesterday. Ladies and children took trip after trip around the city on the belt line cars, and greatly appreciated the novelty and comfort of their surroundings.”

A car- or trolley-barn had to be built to accommodate the new vehicles and a site opposite the fairgrounds was chosen. A one-story building, with an adjacent office, with room for the service and storage of up to twelve cars, was constructed where the Trolley Barn and the South Station restaurant are now located on South Main Street. Another barn was built in West Rutland near Marble and Depot streets. It was here that the additional open summer cars, which were later added to the fleet, were stored.

Moving on out

While the Chittenden Power Company, under the direction of one Mr. William Barstow of New York City and Chittenden, Vt., was constructing the Chittenden Dam, 250 men were constructing bridges and wooden trestles, building concrete abutments, pouring fill, grading the ground, and lying new western-running rails. Upon the dam’s completion in 1902, those 45 construction workers moved onto the rail project helping to bring, by 1906, a total of 35 miles of track and 26 cars into service. At this time, four power, light, and rail companies around Rutland consolidated into Rutland Railway, Light & Power Co. which now owned and operated service lines to Castleton, Fair Haven and Poultney. A seasonal spur up what is now Route 30 also extended to Lake Bomoseen where a recreational area was created.

Larger cars, called Interurbans, traveled at rates of up to 40 mph to Fair Haven and Poultney carrying both passengers and freight. One story Rutland Historical Society curator, Jim Davidson, tells is of a phone call from a Poultney resident to a clothing store in Rutland: Please put a pair of boots from the clearance sale on the 240 Trolley to Poultney.

At the height of the trolley era between 1913 and 1916, the system carried almost 3 million passengers annually. With a record income of $50,330 in 1914, statistically, according to ridership, income, number of cars, and mileage, Rutland’s was the largest trolley system in the state. And although the limited research for this article showed no evidence for residents moving out of town (into the “suburbs”) due to the availability of transportation into the city, in other cities this was certainly the case. It’s probably safe to assume this happened here also. But it was a definite boon to the stone workers who used the line to reach their jobs in the quarries in West Rutland, Fair Haven and Poultney.

And of course, as evidenced by some photos and news clippings from the era, there was the occasional accident, especially when automobiles began to share the roads after 1910. In approximately 1915, Father Francis McDonough, who grew up on Burnham Avenue in Rutland, began riding the electric cars up front with the drivers. Recording his memories of this “thrilling experience,” he tells one story of how he saved the day:

“There was no one in the car except the motorman and myself. It was a rainy evening in the fall and the leaves were falling and as the car would crush the leaves on the rails they would become very greasy. Then the motorman would apply sand to the rails to get traction or to slow down. We were going down Crescent Street from Church Street. There was a very slight incline downward and the motorman began to apply the airbrake to slow down for a very sharp turn onto Grove Street. When he applied the airbrake, nothing happened; the wheels went into a skid because there was no sand in the sandbox at the front of the car. The motorman asked me to get some sand quickly from the sand box at the back of the car and bring it to the front… which I was able to do just in time so that the care gracefully made the curve without jumping the tracks and possibly tipping over, doing some damage and perhaps injuring both of us.”

Pushed off the road

The popularity of automobiles after WWI began the decline of the trolleys, so much so that by 1919, income had dropped over $10,000 from four years previously, and over the next five fell into a deficit of over $3,000. However, the summer trolleys were still popular as townspeople loved to ride in the open-air cars out to the lake on a summer evening.

However, on July 6, 1924 the last trolley rode to Fair Haven and Poultney. In December of that year, no more trips were scheduled between Rutland and West Rutland, and after one last accommodation for Christmas shoppers, all in-town services were halted on December 26. (Two days later however, a motorbus began operating on the exact same route.)

All the rails were pulled up between West Rutland, Castleton, Fair Haven, and Poultney by the spring of 1925. However, as was discovered in 2013, the rails in Rutland were just covered over, providing some track for an imaginary trip into a world bygone where “high speed” travel was new and exciting, and far more friendly.

Originally published in the Rutland Reader, June 18, 2014